CNA - Political Islam: Why the religious conservatism wave is rising in Malaysia but ebbing in Indonesia

Political Islam: Why the religious conservatism wave is rising in Malaysia but ebbing in Indonesia

In the first of a five-part series on political Islam in Southeast Asia, CNA examines the rise of religious conservatism in Malaysia, why neighbouring Indonesia is seeing a contrasting picture, and what these trends could mean for these countries.

A group of young men chatting at a hut with Parti Islam Se-Malaysia (PAS) flags in the background in Kuala Terengganu. (Photo: CNA/Zamzahuri Abas)

Listen to this article

29 Mar 2024 06:00AM(Updated: 03 Apr 2024 09:16AM)

KOTA BHARU, Kelantan: In a bustling central market in Kuala Terengganu, cracker seller Mdm Raqiah Abdullah flipped through pages of the Quran - the Muslim holy book - as she sat on a rickety stool.

The Quran was wrapped in a green cloth with a white circle in the middle - the flag of conservative party Parti Islam Se-Malaysia (PAS).

ADVERTISEMENT

“We are Muslims, so it is our duty to support PAS,” said the 69-year-old.

“I think if we want to be good Muslims, in this life and the hereafter, we have to follow teachings of PAS and its leaders, like Tok Guru Hadi,” claimed Mdm Raqiah, referring to PAS president Abdul Hadi Awang, a renowned cleric who has led the party for more than two decades.

Mdm Raqiah is a lifelong hardcore supporter of the Islamist party. However, she said that among her community in Kuala Terengganu, it was only in the last five years or so that supporting PAS has become popular and mainstream.

Mdm Raqiah Abdullah has been a hardcore Parti Islam Se-Malaysia (PAS) supporter throughout her life. (Photo: CNA/Zamzahuri Abas)

Mdm Raqiah Abdullah has been a hardcore Parti Islam Se-Malaysia (PAS) supporter throughout her life. (Photo: CNA/Zamzahuri Abas)Observers note that this shift in support was due to problems within the country’s oldest party United Malays National Organisation (UMNO) and graft cases among its leadership, such as the 1Malaysia Development Berhad (1MDB) scandal involving former Malaysia prime minister Najib Razak.

“Previously, the rivalry between UMNO and PAS in Terengganu was fierce - there were different mosques, villages and even eateries for the supporters of each of the parties. But now, almost everyone seems to be united behind PAS, with thanks to God,” she said.

Between 1974 and 2013, the UMNO-led Barisan Nasional (BN) coalition ruled the Terengganu state government except for a stint between 1999 and 2004 when Mr Abdul Hadi served as chief minister under the Barisan Alternatif coalition.

However, since the 2018 General Election when BN lost power, PAS and its Perikatan Nasional (PN) coalition have maintained control of the Terengganu state government.

Related:

In recent years, PAS’ popularity has seemingly grown beyond its peripheral supporter base and the party has become the foremost choice for many Muslims living in the rural Malay heartland.

In an interview with CNA, PAS central committee member Muhammad Khalil Abdul Hadi outlined that the party grew in popularity recently due to pull and push factors.

Mr Muhammad Khalil, who is also the son of party president Abdul Hadi, stressed that the party’s “consistency in upholding the rights of the Malays and Muslims” may have attracted voters.

Mr Muhammad Khalil is the eldest son of Parti Islam Se-Malaysia (PAS) president Abdul Hadi Awang. (Photo: CNA/Zamzahuri Abas)

Mr Muhammad Khalil is the eldest son of Parti Islam Se-Malaysia (PAS) president Abdul Hadi Awang. (Photo: CNA/Zamzahuri Abas)“The values of race and religion are absolutely important for the Malay Bumiputera population, and we have not shifted our stance on this since the party was formed and this is a key factor,” said the exco member of Terengganu’s information, preaching and Syariah empowerment arm in the state government.

“There are also push factors - for instance the failure of UMNO as a party to fulfil its obligations in defending and upholding the principles of Islam and defending the rights of Malays,” he added.

Political analyst Norshahril Saat, senior fellow at ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute, told CNA that in recent years, PAS has strengthened its core power base in the northern states and the east coast while making inroads in other parts of Peninsular Malaysia.

“There are many ways of explaining it. One could be that there is this fear that the electorate is growing conservative, particularly among the Malays, and they are now buying into the argument that PAS has been proposing over the years of Islamisation, promoting Syariah laws and so on,” said Dr Norshahril.

“But the other argument could be the lack of alternatives. The Malays have always been supportive of UMNO and they see UMNO as the main party for the Malays and Islam. But now given their problems, the next best alternative is Parti Pribumi Bersatu Malaysia (Bersatu) and of course the party with a longer history is PAS,” he added.

Dr Norshahril Saat is also coordinator at the regional social and cultural studies programme at ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute. (Photo: CNA/Zamzahuri Abas)

Dr Norshahril Saat is also coordinator at the regional social and cultural studies programme at ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute. (Photo: CNA/Zamzahuri Abas)On the contrary, the elections in Indonesia last month appear to show that identity politics there has ebbed, despite initial worries that it could have been marred by religious conservatism.

Dr Norshahril said that identity politics was “somehow cancelled out” across the candidates in the Indonesian polls.

“We don't really see similar identity politics being played out in this year’s elections compared with 2019 and 2014. It could mean that the candidates themselves have equipped themselves very well,” said Dr Norshahril.

“So in this way all the candidates have somehow shored up Islamic support and hence we don't see identity politics being used to attack one another,” he added.

A closer look at Indonesia’s situation

In neighbouring Indonesia, concerns over the rise of political Islam and religious conservatism, especially in the lead-up to its latest election last month, appear to have cooled.

All three pairs of presidential and vice-presidential candidates did not succumb to the use of identity politics to garner votes, observers noted.

The three pairs are: Former Jakarta governor Anies Baswedan who teamed up with chairman of the Islamic National Awakening Party (PKB) Muhaimin Iskandar; current Defence Minister Prabowo Subianto and Solo mayor Gibran Rakabuming Raka; as well as former Central Java governor Ganjar Pranowo who ran with former member of PKB Mahfud MD.

The winning duo of Mr Prabowo and Mr Gibran have never been members of Islamic parties, unlike the other two pairs of candidates.

There was worry that the election would be marred by religious conservatism especially since identity politics dominated the 2019 presidential and legislative elections and Jakarta’s 2017 gubernatorial elections.

Mr Ujang Komarudin, a political Islam expert from Jakarta’s Al Azhar University, believes some political groups want to enforce Islamic ideologies but struggle to win in elections because Indonesian society is heterogeneous.

"Objectively speaking, there are indeed people or groups that fight for an Islamic ideology or political Islam.

"But if we look at the Islamic community, Islam itself here is heterogeneous. It is not homogeneous,” said Mr Ujang.

And although about 87 per cent of Indonesia’s over 270 million people are Muslims, many are not pious, Mr Ujang added.

Many Indonesians practise a moderate form of Islam or are Muslims according to their identity cards but do not really practise the religion.

“This impacts the behaviour of the voters and their choice (during elections),” said Mr Ujang.

Beyond that, analysts told CNA that the differing ideologies of various Islamic political groups and their inability to garner mainstream support as well as the country’s foundational philosophical theory of Pancasila appear to counter the threat of rising conservatism in Indonesia.

DIFFERING IDEOLOGIES GOVERNING ISLAMIST POLITICAL PARTIES

Mr Ujang believes that the Islamist political parties in Indonesia are not united and have differing ideologies. This is unlike in Malaysia, with its dominant Islamist party, the Parti Islam Se-Malaysia (PAS).

“For example, PKB and the National Mandate Party (PAN), do they function based on their ideologies? I think not,” said Mr Ujang.

“They function based on interests, whether when forming a coalition or campaigning. They don’t highlight Islamic values but general or universal values if they talk about Islam.”

There are currently nine political parties in the Indonesian parliament.

Five of them are nationalist parties, and four of them have Islamic ideologies, namely PKB, PAN, the Prosperous Justice Party (PKS) and the United Development Party (PPP).

Only PKB showed a significant increase in votes in last month's legislative elections, making it the fourth-largest party in the upcoming 2024-2029 parliament, whose members will be inaugurated in October.

It was the fifth-largest party in parliament based on the results of the 2019 elections - behind the Indonesian Democratic Party of Struggle (PDI-P), Golkar, Gerindra and National Democratic Party (Nasdem).

“Regarding the legislative election results, thank God. We at PKB are grateful.

“Because we are led by Mr Muhaimin, who is Mr Anies's vice-presidential candidate, we received a significant coattail effect,” said Mr Zainul Munasichin, secretary of PKB’s election-winning unit.

Coattail effect is the tendency for a political party figure to attract votes for other candidates from the same party.

In the recent election, Mr Anies and Mr Muhaimin were backed by the coalition of PKB, PKS and nationalist party Nasdem.

Before the coalition was formed, some analysts opined that PKB and PKS would not be able to work together because they believed in a different form of Islam. But PKB’s Mr Zainul told CNA that his party’s alliance with PKS was “purely tactical”.

Meanwhile, PAN - which backed Mr Prabowo and Mr Gibran - was founded by people who were members of Indonesia’s second-biggest Islamic organisation, Muhammadiyah.

PAN’s secretary general Eddy Soeparno said it performed slightly better in February’s election compared to five years ago because of the perception then that it was right-wing due to its founder’s participation in events attended by hardline Islamic groups.

The remaining Islamist party in parliament - the PPP - is the oldest and has existed for 51 years.

It was one of the only three political parties during the regime of Suharto, along with nationalist party Golkar and PDI, now named PDI-P.

But in recent years, it has lost ground.

Mr Muhammad Romahurmuziy, chairman of PPP’s advisory council, attributed this to many factors.

One was because it does not have a strong leading figure and political machinery.

“We would have to undertake a major reorientation in the next party congress,” Mr Romahurmuziy told CNA, adding that it is due in December next year but could be brought forward due to the latest election results.

According to the official results released by the Indonesia's General Elections Commission, PPP did not meet the minimum threshold of 4 per cent to enter the House of Representatives. This is the first time since its establishment in 1973 that the party will not be represented in parliament, although PPP will challenge the election results at the Constitutional Court.

Mr Adi Prayitno, a political Islam expert from Universitas Islam Negeri Syarif Hidayatullah, surmised that parties operate based on interests rather than ideologies because Indonesia has a multi-party presidential system.

“There is a tendency that everyone is just chasing electoral votes,” said Mr Adi.

“In Indonesia, everything is being measured by political interests and not ideology.”

PANCASILA A WAY TO REIN IN IDENTITY POLITICS

In line with this, Mr Ujang from Al Azhar University noted that Islamic conservatism is not a selling point to most Indonesians.

“I don’t think conservatism is a threat in Indonesia because the democracy in Indonesia is built on Pancasila,” said Mr Ujang.

Pancasila is Indonesia’s ideology, which consists of five principles: Belief in one and only God, justice and civilised humanity, unity of the country, democracy guided by the inner wisdom among representatives, and social justice for all Indonesians.

“And Pancasila is the home of all religions in Indonesia, creating harmony,” Mr Ujang said.

Mr Ahmad Khoirul Umam, a political lecturer from Islamic university Paramadina in Jakarta, concurred.

“This is what makes the character of Islam in Indonesia very different from others in the region,” he said.

Mr Umam said Pancasila has become an identity of Indonesia, with its history dating back to the country’s first president, Sukarno.

Dean of Islam Nusantara faculty at Nahdlatul Ulama Indonesia University Ahmad Suaedy told CNA that Pancasila is the reference point for every political group because it encompasses various ideologies.

“So, in Indonesia, there are many religious elements which are used by the state. But they are not part of the political symbol because of Pancasila,” said Mr Ahmad.

In a country with about 1,300 different ethnic groups, the analysts believe that Pancasila has been a crucial element in keeping the country united.

“We are grateful Indonesia has Pancasila, which unites different religious communities. So there is no reason for Islam to be dominant and a threat,” said Mr Ujang.

Expand

Related:

PAS HAS GROWN FROM STRENGTH TO STRENGTH

Following Malaysia’s 2022 General Election, PAS is arguably the strongest individual party in the country at the federal level.

It now holds 43 out of 222 seats in parliament and its presence is even bigger than Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim’s Parti Keadilan Rakyat (PKR), the multiracial-centric Democratic Action Party (DAP) as well as UMNO. Malay nationalist party UMNO previously dominated Malaysia politics between 1957 and 2018.

At the federal level, PAS leads the opposition coalition PN together with the Malay nationalist party Bersatu.

PAS also scored big in the six state elections held in 2023, winning 105 out of 127 seats it contested. It led a clean sweep of all 32 state seats in Terengganu under the PN banner, winning 27 of those while the remaining five were won by Bersatu.

PAS is also currently heading the government in four states - Terengganu, Kelantan, Kedah and Perlis - in the north and known as the Malay heartland.

Buoyed by recent political gains, the conservative party is now eyeing to form the government at the next General Election.

Parti Islam Se-Malaysia (PAS) president Abdul Hadi Awang at the party's 69th annual congress in Shah Alam, Selangor on Oct 21, 2023. (Photo: CNA/Fadza Ishak)

Parti Islam Se-Malaysia (PAS) president Abdul Hadi Awang at the party's 69th annual congress in Shah Alam, Selangor on Oct 21, 2023. (Photo: CNA/Fadza Ishak)Observers said while the party has publicly spoken about trying to appeal to non-Muslim voters to garner support from the mainstream, it has struggled to pull away from its hardline approach to political Islam - a big part of the party’s DNA under Mr Abdul Hadi’s leadership.

This is reflected in the party’s recent doubling down on matters such as the implementation of Syariah laws, education policies as well as social issues. PAS also has a penchant of calling non-Muslims “kafir” - or infidels - which is often seen as an insult.

Political analysts acknowledged that the party’s hardline approach on certain issues has boosted the support for PAS among the Malay-Muslims, which accounts for more than 60 per cent of the national population.

However, there is a concern that if PAS persists with this conservative brand of Islam, it could polarise the country and pull citizens apart along religious and ethnic lines.

Related:

Political analyst James Chin, professor of Asian studies at the University of Tasmania and senior fellow at the Jeffrey Cheah Institute on Southeast Asia, told CNA that divisive Malaysian politics has led to a fractured society.

“People don't realise that the country is actually fractured into very different versions of Malaysia. If you look at the Malaysian Parliament now, the biggest bloc is actually PAS and PAS stands very clearly for negara Islam Malaysia, or Islamic State of Malaysia.

“And the second biggest bloc is actually the DAP which stands for a multiracial, hybrid state, not Islamic but not secular either. So you can see that these two blocs have nothing in common and yet they command the two biggest blocs in the Malaysian parliament,” he added.

The DAP is part of the Pakatan Harapan coalition led by Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim.

PAS HAS OVERTAKEN UMNO AS THE PARTY OF CHOICE AMONG MALAYS

This transfer of support from UMNO to PAS in the Malay heartland is a huge political shift seen since 2018.

Associate Professor Dr Mohd Yusri Ibrahim, chief researcher for think-tank group Ilham Centre, told CNA that for more than six decades post-independence, the Malay community gravitated towards UMNO.

He said Malay nationalism was the raison d’etre for UMNO’s formation - focused on increasing social mobility among the community.

However, he opined that corruption scandals - such as the 1MDB case involving jailed former prime minister Najib Razak - has caused the party to lose legitimacy and with it, its brand of ethnonationalism. Meanwhile, PAS’ conservative Islamist ideology has come to the fore.

Associate Professor Dr Mohd Yusri Ibrahim is based in Kuala Terengganu and does field research in villages across the east coast of Peninsular Malaysia. (Photo: CNA/Zamzahuri Abas)

Associate Professor Dr Mohd Yusri Ibrahim is based in Kuala Terengganu and does field research in villages across the east coast of Peninsular Malaysia. (Photo: CNA/Zamzahuri Abas)“Since the 2018 General Election, we have seen based on our research on the ground, in the villages, that support for PN and PAS grows day by day, while support for UMNO has waned,” said Assoc Prof Mohd Yusri.

He added: “Now, Malays who pride themselves on their ethnicity and religion, based on Malay-ism and Islam-ism support PAS because PAS is the one party now flying the flag for both these issues.”

A politician who has seen this shift first-hand is Arau Member of Parliament Shahidan Kassim. The influential warlord, who was axed from the last general election candidate list by UMNO president Ahmad Zahid Hamidi, switched to PAS before nomination day.

After trading party colours, Mr Shahidan clinched the Arau federal seat in the state of Perlis by a majority of more than 23,000 votes, having garnered only slim majorities of around 1,000 to 4,000 votes during the previous two national polls.

In an interview with CNA, Mr Shahidan said that PAS has become accepted by Malay Muslims across the country and has successfully managed to persuade supporters of other parties as well as those in the middle ground.

“They rejected UMNO because of the leadership tussles and the party was not seen as representing their interests anymore,” said the former chief minister of Perlis, who was also Minister in the Prime Minister’s Department.

Former Barisan Nasional warlord Shahidan Kassim switched sides to Perikatan Nasional before the 2022 General Election after he was axed from the candidate list by United Malays National Organisation (UMNO) president Ahmad Zahid Hamidi.…see more

Former Barisan Nasional warlord Shahidan Kassim switched sides to Perikatan Nasional before the 2022 General Election after he was axed from the candidate list by United Malays National Organisation (UMNO) president Ahmad Zahid Hamidi.…see more“The PAS supporters are loyal and will always vote for the party. These extra votes (I received) were from (former) UMNO supporters and those who were on the fence,” Mr Shahidan said.

Identity politics is closely linked to race and religion among Muslims in Malaysia and Indonesia, according to a study released by American think-tank Pew Research Centre in 2023.

The study, which surveyed 13,122 adult respondents across six Asian countries between June and September 2022, found that 86 per cent of Muslim respondents in Indonesia said it is “very important” to be a Muslim to be truly Indonesian, which is closely followed by 79 per cent of Muslim respondents in Malaysia who also equate the religion to national identity.

Assoc Prof Mohd Yusri said that PAS, especially in recent years, has been shrewd in recognising this close relationship between identity politics and religion, and it has crafted its campaign agenda to play on these sentiments.

“PAS played up the sentiments of race and religion, and this is a proven strategy that works,” he said.

“They play up fear that Malays will lose their special rights (as enshrined in the constitution) and that Islam is being threatened. This is a deadly weapon to pull support,” added the policy studies programme lecturer at Universiti Malaysia Terengganu’s (UMT) faculty of business, economics and social development.

Meanwhile, PAS’ strength has also grown within the PN coalition and many observers feel it has solidified its position as the “big brother” in its partnership with Bersatu.

Bersatu leaders Muhyiddin Yassin and Hamzah Zainudin are seen as the de facto leaders of PN and possible prime minister candidates if the coalition comes into power.

However, observers noted that Bersatu’s strength is waning following internal strife as six of its Members of Parliament have pledged support for the unity government led by PM Anwar.

PAS has also put forth professional leaders with executive experience such as Terengganu chief minister Ahmad Samsuri Mokhtar, who is being touted as a possible prime minister candidate for the future.

Related:

PAS’ ascension has not gone unnoticed among politicians in the unity government.

Deputy minister for trade and industry Liew Chin Tong from DAP believes that PAS has overtaken Bersatu as the stronger force in the PN coalition.

“Bersatu is on decline and Bersatu is sinking. What is not sinking? What is going to remain as a potent force is PAS,” said Mr Liew.

“And eventually, Bersatu will be subsumed under the PAS brand,” added the Member of Parliament for Iskandar Puteri.

CAN PAS GO MAINSTREAM AND GOVERN ON ITS OWN?

While PAS is on the rise, some have observed that perhaps the Islamist party has reached its saturation point and the maximum level of support it could garner on the basis that it would not be able to form the next government on its own, unless it wins the hearts and minds of non-Muslims as well as Malays in urban areas.

During the party’s congress in 2023, Mr Abdul Hadi acknowledged in his speech that the party needed to work on winning over non-Malay and non-Muslim voters to make greater inroads at the next polls.

However, external observers believe this is an uphill task given the party’s core position.

DAP’s Mr Liew said he believed that PAS had peaked in the recent polls and it is now “on a decline” as it is unable to offer voters of other races, including those in Sabah and Sarawak, a brand of politics that is acceptable.

Democratic Action Party (DAP) deputy secretary-general Liew Chin Tong. (Photo: CNA/Zamzahuri Abas)

Democratic Action Party (DAP) deputy secretary-general Liew Chin Tong. (Photo: CNA/Zamzahuri Abas)“If PAS chooses to continue with its hardline position (on Islam), it will be able to keep what it has (control over northern states) but it will not have a national impact. Because in Malaysia, there’s a huge middle ground among the Malays and also among Malaysians.

“The Malay middle ground and the multi-ethnic Malaysian electorate would not buy into a hardline position,” said Mr Liew, who wrote an academic thesis on PAS and democracy that was published in 2006.

PAS’ hardline position on political Islam is said to have been consolidated in 2015, when the party’s spiritual leader Nik Aziz Nik Mat died and the faction of the party which comprised of non-cleric professionals who advocated an inclusive approach of Islam left to form Parti Amanah Negara (Amanah), one of the key component parties of PM Anwar’s Pakatan Harapan coalition.

These included Amanah president Mohamad Sabu and current Minister of Health Dzulkefly Ahmad.

The exodus of this group, dubbed the Anwarinas faction for their support of Mr Anwar, paved the way for Mr Abdul Hadi to accelerate an ideological convergence in PAS which reflects his far-right ideals.

A key ideological difference between Mr Abdul Hadi and the late Nik Aziz was in their approach to non-Muslims. The latter saw non-Muslims not as a threat to the party and Islam, while Mr Abdul Hadi - who is more exclusivist - has publicly spoken against the appointment of non-Muslims in key political positions and also claimed that those responsible for corruption in the country mainly comprised of them.

Mr Muhammad Khalil of PAS told CNA that even today, the party’s ethos in political Islam is that it believes that the leaders of various segments of government across the country should be Malay-Muslims.

“An important principle in political Islam in the Malaysian context, is the principle of which race is most influential, because there are some people who try and create confusion by saying that PAS is a party that is racist, because it upholds rights of Malay bumiputera, but we must distinguish between fighting for the rights of a certain race, and being racist.

“In the context of Malaysia, the majority is the Malay bumiputera who are Muslims. This is why PAS is consistent in its stance that in Malaysian politics, its leaders must be those who are Malay-Muslims, because they are the majority and dominant race in Malaysia,” he added.

Mr Muhammad Khalil cited how in countries like Japan and France for instance, the heads of the governments are of Japanese and French ethnicity respectively.

Mr Abdul Hadi has also on various occasions used DAP, which is led mainly by ethnic Chinese politicians, as a scapegoat and warned that the party is a major threat to Islam.

Mr Mohd Firdaus Talha, a 21-year-old who studies at a religious school in Kelantan which is funded by PAS, told CNA that he voted for PAS as he did not want DAP and its “liberal ideals” to govern the northern state.

Politics researcher Assoc Prof Mohd Yusri pointed out that the sentiment is widespread among youths in Terengganu and Kelantan, and it is a perplexing view given that no DAP candidate contested in these states in the 2023 polls.

“When we ask young voters why they want to vote for PAS, they said it's because they want to bring down DAP. We are shocked, because in Terengganu and Kelantan, DAP does not have any presence,” he said.

Mr Liew had been a DAP member between 2008 and 2015, when PAS, DAP and PKR were united under the Pakatan Rakyat coalition. The alliance made inroads but failed to topple the UMNO-led BN government.

“During that period, the dominant idea within PAS was to try and ... win the middle ground, to be a national party for the mainstream. But this push eventually led to the split within the party and the hardliners took charge while those who were trying to mainstream the party left and formed Amanah,” he added.

“Now PAS has to go through a process of renewal on its current leadership …. At some point the party will have to renew its ideas and rethink its approach. There needs to be a new generation that comes out and projects a different image for the party to win across racial lines, to win the Malay middle ground and to win across the South China Sea (support in East Malaysia),” said Mr Liew.

PAS DOUBLING DOWN ON HARDLINE ISLAM

On the surface, it may seem like PAS is indeed making efforts in its attempt to reach out to the non-Muslims.

In late 2023, the party issued a statement wishing Christians a Merry Christmas. The party previously said sending such greetings was against the teachings of Islam and has elements of syirik (idolatry).

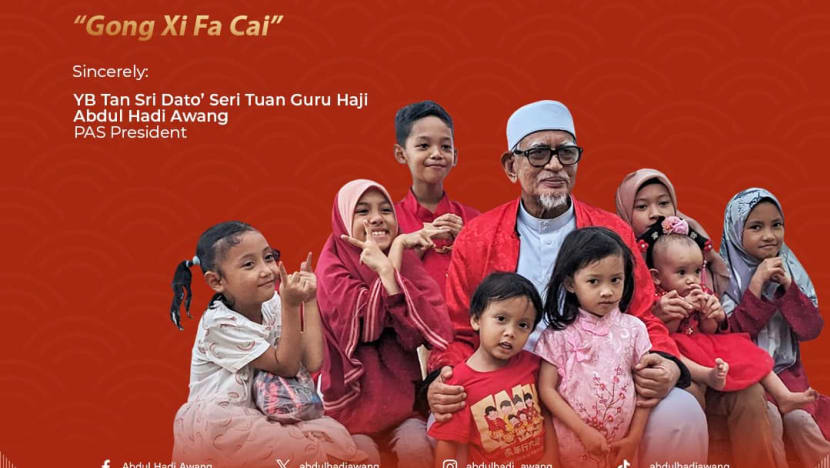

A Chinese New Year banner posted on Parti Islam Se-Malaysia (PAS) president Abdul Hadi Awang's Facebook page in February. (Photo: Facebook/Abdul Hadi Awang)

A Chinese New Year banner posted on Parti Islam Se-Malaysia (PAS) president Abdul Hadi Awang's Facebook page in February. (Photo: Facebook/Abdul Hadi Awang)Also in February, Mr Abdul Hadi in his Chinese New Year message said that all Malaysians should aspire towards a prosperous nation in which all communities live in peace and harmony.

"The diversity of races and ethnicities is celebrated as a sign of Allah's magnificence and is part of nature in the creation of humanity.

"Islam, which is the guiding principle of PAS, guarantees justice, peace and well-being for all races and religions in this country," Mr Abdul Hadi wrote.

Mr Shahidan - the Arau MP - said these are steps to show that PAS aims to unify Malaysians rather than sow division.

“Islam is a religion that unites. We are good with everyone. We never planned to bring anyone down. We only plan to fix the beliefs (akidah) of the Muslims,” he added.

Analysts said these moves show PAS understands the political reality of needing support from the non-Malays to govern in Malaysia.

However, they pointed out that these efforts are often cancelled out by the party members’ firm stance on hardline Islam, which rears its ugly head across countless political issues.

For instance, PAS religious council chief Ahmad Yahaya earlier in March spoke out against the education ministry’s directive that school canteens would continue operating during Ramadan - the Muslim fasting month - so that non-Muslim students could have their meals.

Mr Ahmad said the closure of canteens should be a societal norm to respect Muslims who were fasting.

The party has also overseen the closure of lottery outlets across the four states it governs, as part of its efforts to phase out gambling, which is prohibited in Islam.

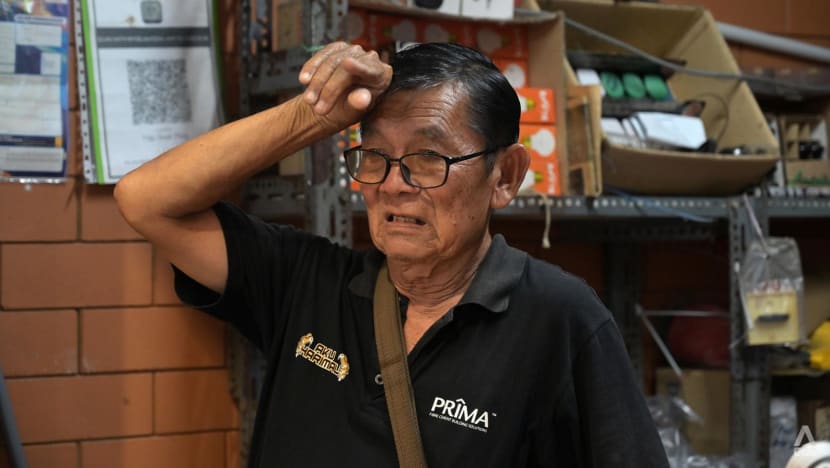

Mr Yap Suat Ping, who sells Chinese-language newspapers in Terengganu, told CNA that there is an element of “unfairness” in this rule.

Mr Yap Suat Ping sells newspapers at Kuala Terengganu's bustling central market. (Photo: CNA/Zamzahuri Abas)

Mr Yap Suat Ping sells newspapers at Kuala Terengganu's bustling central market. (Photo: CNA/Zamzahuri Abas)“It’s ok for PAS to prohibit Muslims from gambling, but non-Muslims should be free to engage in this activity as well if they wish,” said the 70-year-old.

PAS members have also repeatedly spoken against the hosting of concerts by foreign artists such as British band Coldplay and Korean girl group Blackpink.

Mr Abdul Hadi was also recently rebuked by Selangor ruler Sultan Sharafuddin Idris Shah over the PAS president’s criticism of an apex court ruling that found the state of Kelantan had overreached in its Syariah law implementation.

This came after the Federal Court ruled on Feb 12 that Kelantan, governed by PAS, cannot expand the jurisdiction of its Syariah law to include criminal acts already covered by federal powers.

In the article published on PAS' online news portal, Mr Abdul Hadi wrote that the country’s monarchs need to “have a vision towards the afterlife” and not only on worldly matters, saying they would be judged by God on how they used their power and position while alive.

A five-page letter from the palace of the Selangor ruler – who is also chairman of the National Council of Islamic Religious Affairs - outlined that Mr Abdul Hadi’s statements were “very inappropriate and rude”.

Related:

RELIGIOUS RHETORIC COULD HINDER DEMOCRACY

However, Ilham Centre’s Assoc Prof Mohd Yusri said such religious rhetoric does strengthen the party’s support among its core voter base.

“PAS has influence over various pockets of Muslim society - the schools, the Tahfiz (Quran learning centres), as well as community events such as funerals and weddings. Its grassroots is felt throughout the community, and when leaders issue statements playing on these sentiments, the information is disseminated quickly and effectively,” he said.

However, Assoc Prof Mohd Yusri explained the downside is that voters in the Malay heartland tend to be buoyed by religious rhetoric over election candidates who would be better at governance, and this hinders the democratic process.

“In Malaysia politics, especially in the Malay heartland, what matters more is your skill to manipulate religious and racial sentiments. You don’t have to be a good governor or administrator, and you can win,” said Assoc Prof Mohd Yusri.

He cited a Ilham Centre study before the 2023 state elections which found residents in the states of Kelantan, Terengganu and Kedah were least happy with the quality of state governance.

In spite of this, PAS defended all three states with larger majorities at the polls.

The researcher expressed hope that Malaysia could take a leaf out of Indonesia, where political Islam and conservative politics did not reign supreme in the recent 2024 Presidential Elections held in February.

“There was no play on religious sentiment. There was support by Islamist groups for Anies (Baswedan) but it was not substantial enough to win the elections,” said Assoc Prof Mohd Yusri.

“Even so, for a huge segment of voters in both Malaysia and Indonesia, it is easy for just about anyone to manipulate religious sentiments and ethnic sentiments to get quick support.

“That’s why we must work hard in the Malaysia context in Southeast Asia. We have to educate youths on democracy because if political literacy is high, they will be mature enough to make the right decisions for their future,” he added.

Youths in Malaysia spend a significant amount of time on their smartphones. (Photo: CNA/Zamzahuri Abas)

Youths in Malaysia spend a significant amount of time on their smartphones. (Photo: CNA/Zamzahuri Abas)DAP’s Mr Liew echoed similar sentiments. Muslims in the region are pious but they also want to make a good living for themselves, he said.

“They want upward mobility, they want good governance and they want a hopeful future for their nation,” he said.

“I would think that politicians will have to appeal to voters through a range of issues, through building a more comprehensive policy framework. And eventually articulating hope and not just playing on fear.

“Political Islam has been premised on fear, anxiety and the idea that Islam is under threat. To the younger generation, fear may appeal, but hope is more appealing.”

Additional reporting by Rashvinjeet S Bedi

Ulasan

Catat Ulasan